26. Nov. 2024

Professor Eric Głowacki is a physical chemist by training, but over the past fifteen years, his work has gradually shifted to biomedicine. After spending seven years in Austria and five in Sweden, he settled in Brno with his wife and collaborator. He currently leads the Bioelectronic Materials and Systems research group at CEITEC BUT, focusing on the development of biomedical devices and procedures that can wirelessly stimulate the nervous system. Eric Głowacki is currently the recipient of an ERC grant for the OPTEL-MED project (Optoelectronic Medicine – Control of Nerve Cells by Light).

In Brno, we can conduct all our research in one place

You've been in Brno since 2020. What attracted you here?

After five years in Sweden, I received an interesting offer from CEITEC BUT in Brno, and I immediately liked it here. The facilities and laboratories, especially the cleanrooms at CEITEC Nano, are truly exceptional. I gradually realized that Brno offers many additional advantages. In our research at the intersection of physical and biomedical sciences, we need the collaboration of biologists, doctors, and opportunities for animal and clinical research. All of this is available here in Brno. In Sweden, we had to conduct all experiments abroad or in Stockholm, which was organizationally and logistically challenging. The ability to conduct all our research in one place was the deciding factor to move the group from Sweden to Brno.

Implantable devices charged by a mobile phone

It seems like the OPTEL-MED project takes up most of your time now. Can you tell us more about it?

The OPTEL-MED project stems from research I've been working on for nearly ten years. The idea is to safely power implantable components in the human body. We can implant many things into the human body, but we are limited by space. One challenge is figuring out how to miniaturize the components that can be surgically implanted in the target area. Many people in biomedical engineering focus on wireless power transfer for components, especially how to transmit energy not only under the skin but also through thicker tissue, such as under the skull. Ten years ago, we introduced the concept of using infrared light, essentially optical light, to power a component in a simplified way with a solar cell. There are wavelengths that can penetrate tissue with minimal loss and, more importantly, in an absolutely safe manner. If you place your finger on your mobile phone flashlight, you can see red light passing through the finger. This insight led us to the idea of developing neurostimulation implantable devices that can be powered externally using simple light sources.

And a mobile phone with a flashlight is something everyone has in their pocket.

Exactly. We can create a simple app that modulates the light for digital information transfer. The patient could then place their phone on the implant and activate it whenever they need it.

In a year, we’ll be certain about the next steps

What stage is the research at now?

We have completed several trials proving that this method works. The OPTEL-MED project aims to demonstrate this method in several animal models, and we’ve succeeded. We have tested it on insects and rodents and are preparing for tests on pigs, which is the final step before clinical application. Testing on large animals is financially and time-intensive, so we want to pinpoint a specific application before diving into it. Scientifically, it’s a success. We’ve published many quality papers, and the response from the scientific community has been very positive. However, now we are considering which applications make the most business sense. OPTEL-MED ends at the end of 2025, which is just around the corner. So we’re contemplating what the next step will look like. I think within a year, we’ll know for sure what comes next.

What applications are you considering?

The initial idea was to target the cervical region of the vagus nerve, whose stimulation is used for treating various forms of epilepsy or inflammatory diseases, especially Crohn’s disease. Studies have shown that vagus nerve stimulation completely changed patients' lives, and I’ve met a few such individuals. Currently, it is done by implanting a pacemaker-like device under the collarbone, with wires leading to the vagus nerve in the neck. However, the surgery is highly complex and invasive, with only a few surgeons willing to perform it.

Your stimulator is significantly smaller, so the procedure could be simpler and less invasive?

It’s a plastic component that looks like tape. The thickness is a few micrometers, about a tenth of a human hair. The problem is that the nerve still needs to be isolated, and even with a minimal component, we cannot bypass the complex surgical procedure. Therefore, we are collaborating with surgeons to find an implantation method, as the technology’s success depends on it. We are exploring applications that don’t require such complex surgical implantation.

What other possibilities are there?

We’re also considering stimulating the cerebral cortex. Some of the most interesting indications are psychiatric illnesses, such as depression. Currently, patients visit the hospital weekly for brain stimulation, but with our implant, they could perform the stimulation at home. Also, implantation on the brain’s surface is currently very simple, or at least simpler than implantation on the vagus nerve. We’re also considering applications for chronic pain or migraines.

Passing on knowledge and creatively solving problems is what I enjoy most

Do you encounter ethical questions in your research?

Thank you for asking; it’s an important topic. The established procedure begins with in vitro experiments, then on rodents, and finally on sheep or pigs. We try to reduce the number of rodent models by introducing an intermediate step between in vitro and rodents—specifically, invertebrate models like insects and annelids. We can test new ideas or procedures on grasshoppers and cockroaches. Once we’ve ironed out any issues, we move on to mice or rats. This has significant ethical value, and also financial value, as it allows us to conduct valuable research on grasshoppers, which are inexpensive. It’s essential to me that students can immediately engage in animal research, as experiments with mice require certification, which is difficult to obtain. In general, this is a gentler approach, and I’m trying to popularize this method with invertebrates.

What do you enjoy most about your work?

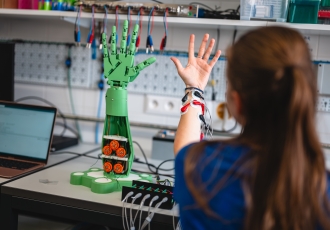

Probably working with students. In recent years, I’ve started teaching biomedical technologies and diagnostics at BUT, bringing students into our group for bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD projects. When someone starts with us on a bachelor’s project and stays, it means we’re doing something right. It’s motivating for me to set up a new experiment with students in the lab and see them gain independence and conduct their own experiments. Passing on knowledge and creatively solving problems is what I enjoy most.

You’re also trying to bring the field of neural engineering to BUT. How is that going?

This year, we ran a summer school of neural engineering at CEITEC BUT, which was hugely successful. We planned it for twelve students but received about fifty applications. This was a surprise but also a boost for us. There is enormous interest in this field, and we’re wondering why Brno doesn’t have a program covering neural engineering. We are trying to turn neural engineering into regular courses. However, we will definitely organize the summer school again, and we’re considering an international course next year.

What takes up more time than you’d like?

In the Czech Republic, probably administration. If the Czech Republic wants to become even more scientifically competitive, it should address this. We still spend an unreasonable amount of time on reporting, filling out tables, and indicators. CEITEC BUT has partially solved this. The administrative and overhead costs here are minimal, but there are still unnecessary national-level obstacles that don’t benefit anyone. I feel that this is increasingly openly discussed in the Czech scientific community, which is positive.

Share

Share